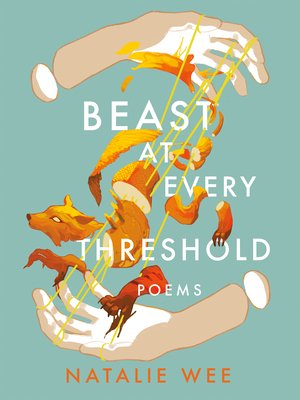

Beast at Every Threshold: An Exploration of the Balance Between Hope and Despair

By Beck Snyder, written October 2022

It has, admittedly, been a while since I decided to sit down and read a collection of poetry for reasons other than needing a good grade on a class assignment. Poetry is one of the realms of writing that often eludes my grasp—not because I don’t want to seek it out, but because fiction and nonfiction pieces usually end up getting there first. When it comes to Natalie Wee’s collection Beast at Every Threshold (2022), however, I immediately knew upon beginning that this was a book that would stick with me as clearly as any beloved fiction adventure from my childhood.

Beast at Every Threshold is best described as a careful balancing act between hope and despair as Natalie wades through both her past and present while considering her potential future. Within her poems, she openly acknowledges and explores the tragedies of life and loss, such as her grandmother’s Alzheimer’s and abuse she herself has suffered. She does not attempt to fool her audience into believing that every problem in life can be solved through having hope, but as she looks into the more depressing aspects of life, she still brings hope into the equation along with a strong sense of reclaiming power, as she does in the poem “Wei Yang Tells Me About Resurrection.” In the poem, she describes the pain that is necessary for resurrection but turns it on its head into using that pain to transform your own life and bring it under control: “Choose a hell / of your own making over the hell that unmakes you.” Her sense of hope also comes to a head in her poem “In My Next Life as a Fruit Tree,” where she muses on her potential next life and what she will become, and while she could choose anything, all she wishes to do is to provide love and care for those who come after her, and to simply exist peacefully: “but I’ll flower one crop each day for as long / as the palm reaching upwards needs something to adore / it.”

It’s a beautiful message that takes the idea of existence and works it into something that we do not have to prove we deserve, but something that we can simply enjoy. Within this collection, Natalie is no stranger to depression and pain, but is not interested in painting a grim, hopeless vision of the world around her. Natalie sees both hope and despair that exists within the world, and because of that, I was left feeling as though I was seeing real, unbridled truth on the pages before me.

Just as Natalie is a master of finding hope within despair, she also works within her poetry to find beauty within the unconventional. This is a theme that comes in right away in the first poem of the collection, “In Defense of My Roommate’s Dog,” which turns the somewhat embarrassing act of a dog humping a stuffed animal in front of guests into a breathtaking exploration of sexual longing and asks the reader why they find shame in masturbation when it is rooted in a longing for love and the need to survive: “Maybe the trade-off for resurrection is / shame vast enough to kill / us.” Natalie has turned this small, everyday act, which most of us would feel awkward about witnessing, into a radical questioning of our values, and why it is that we are so ashamed of basic human nature.

Natalie also continues this theme of unconventional beauty throughout the entire collection, most notably to me in the piece “Inside Joke,” where she uses texting lingo and internet memes, two things which are typically not considered to be poetic, into an exploration of togetherness and adoration.

“tbh, we are so damn lucky to be loved like this

w/ endless ways 2 bless one another

our voices crowned w/ something new

& tender

& no one else’s”

I wasn’t expecting to find a piece within this collection that hit quite so close to home, but as someone on the edge of Gen Z, this piece connected strongly with me as a kind of validation for the way the younger generations share our love and laughter with one another.

Natalie is also heavily interested in exploring immigrant culture and the experience of living separate from yet still connected to one’s home country. Nearly every poem in the collection connects to this overarching theme, whether that connection be overt or subtle. Natalie’s culture and mother tongue bleeds into every word she writes, in a way that proves that she could not separate herself from this aspect of her life. Throughout the collection, she explores the nature of being an immigrant through poems such as “An Abridged History,” “Frequent Flyer Program,” and “Immigrant Aubade,” all of which look into different aspects of her unique-yet-shared experience. Within these pieces there is clear trauma, as she discusses hate crimes and disconnect, but there is also love threaded in between as she connects with other women both within her family line and out of it, who have lived through her pain and understand it, and are all moving toward a more hopeful future of reconnecting and learning to carry the pain without allowing it to become overwhelming.

Another aspect that connects much of Natalie’s work, so much so that she describes herself first and foremost as a queer author, is an exploration of her queerness. Her love poems are unlike any I’ve read before, in a way that allows for tenderness to sit alongside doubt. Natalie writes of love as the very thing that allows her to become real, and the honesty and delicate nature she brings to that admission connected strongly with me as a reader while also taking my breath away. She writes of love as something to hold onto and call her own when everything else falls away, as a final reason to hang on to hope when the world is far too dark to see anything else. All too often, I see queer love described in ways that are meant to prove we are no different than anyone else, but Natalie writes about it as if that difference is the very core element that makes it beautiful and worthy of celebration. She does not shy away from anything risqué—instead, she brings it to light and asks us to celebrate alongside her: she is in love, she is real, she is worthy.

Overall, Natalie’s collection is a stunning look into the different parts of her life, where they connect, where they collide, and how she weaves them all together. It is a breathtaking balance between hope and despair, and a poetry collection that left me reaching out for more only to turn the page and find the acknowledgements waiting. In an age that is all too eager to push queer, immigrant stories into the background, Beast at Every Threshold is an honest, unashamed look at the life that exists around Natalie and one that demands to be listened to.

You can find Natalie Wee’s Beast of Every Threshold: Poems (2022) at Arsenal Pulp Press: arsenalpulp.com/Books/B/Beast-at-Every-Threshold.

Beck Snyder is a senior at Towson University studying both creative writing and film. They are from the tiny town of Clear Spring, Maryland, and while they enjoy small-town life, they cannot wait to get out of town and see what the world has to offer. They hope to graduate by the summer of 2023 and begin exploring immediately afterward. You can find more from Beck at their Instagram, @real_possiblyawesome.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we SPARK and sparkle this year: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.