Yellow Arrow Publishing Blog

Legacy in Bloom: A Conversation with Michele Evans about februaries

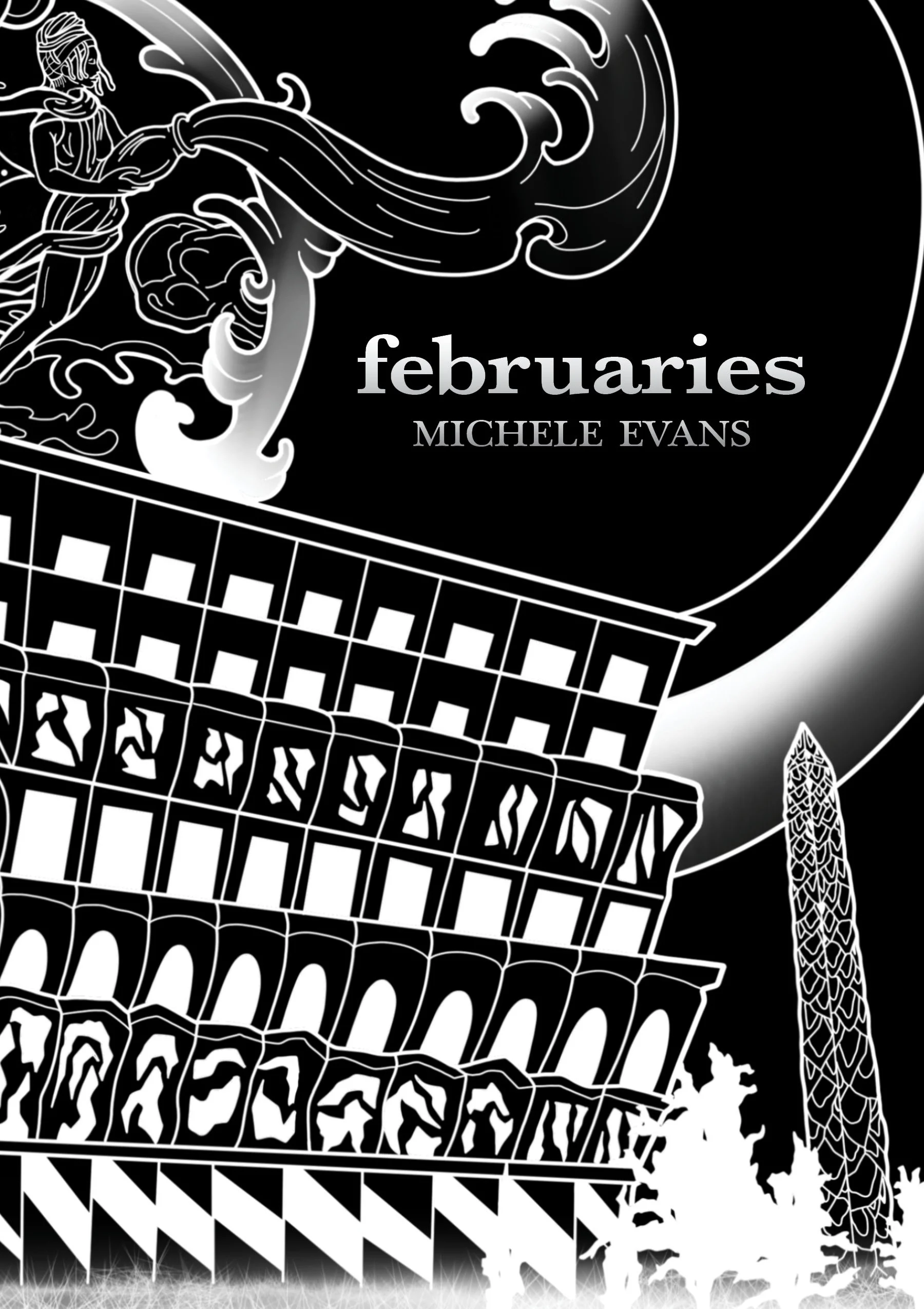

With februaries, poet and educator Michele Evans invites readers into a conversation about art, ancestry, and the everyday acts that keep language alive. In her new chapbook, which will be released by Yellow Arrow Publishing in February 2026, she transforms celebration into conversation, weaving the voices of Black writers, the rhythms of the classroom, and the pulse of her community into a lyrical archive. Her work exists in that generative space between teaching and creating, where reflection becomes ritual and the act of writing becomes a gesture of gratitude.

Photo K. Evans (Instagram @snapsbykee44)

Throughout her teaching career, Evans has cultivated literary appreciation through her dedication to building positive habits and environments for her students, which is highlighted in her involvement in her school’s African American Read-In. In February 1990 the first National African American Read-In was established by the Black Caucus of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE). Twenty-five years after the inaugural event, the English Department at Broad Run High School in Loudoun County, Virginia, where Evans has taught for more than two decades, held its first read-in on February 25, 2015, to celebrate Black History Month.

Evans’ second poetry collection, februaries, emerged from these readings, evolving into both homage and self-portrait. The collection extends Yellow Arrow’s mission through a lens that is as intimate as it is communal. You can preorder a copy of februaries at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/februaries-paperback; the collection will be released February 3.

Evans and Yellow Arrow interviewer, Melissa Nunez, connected to discuss the origins of februaries, the creative lineage of Black women poets, the importance of community and form, and the enduring beauty found in language, legacy, and love.

so when the rain pummels, and the fire burns,

and the wind smacks, and the snow pounds,

and the overseer strikes, this conductor knows

she must be greater than the rest, knows she must

be fearless, boundless, tireless, selfless because

freedom means nothing to one until it means

everything to all.

“≤: less than or equal to?”

Aside from the incredible, notable names already acknowledged in your collection, who are some women-identified writers who inspire you?

In addition to Maya Angelou and Alice Walker who are acknowledged in the collection, there are so many writers that inspire me. Because februaries is a chapbook of poems, I will focus on poets. First and foremost, I wouldn’t be where I am today if it weren’t for my poetry ancestors: Gwendolyn Brooks, Nikki Giovanni, June Jordan, and Audre Lorde. I had the opportunity to meet Giovanni before her death, and I was so awe struck I couldn’t even find the words to tell her how much of an impact her writing has had on me as a black person, a woman, an educator, and a writer. “Changes” and “The Blues” are two of Giovanni’s newer poems from Make Me Rain (Harper Collins, 2020) that really speak to me as an emerging poet. Other living poets who inspire and influence my writing are Rita Dove, Nicole Sealey, Evie Shockley, and Natasha Trethewey.

The concept behind your collection, februaries is resonant and substantive. Can you share the process that brought this collection from idea to completed work?

I am a high school English and creative writing teacher at Broad Run High School. Since 2015 the English Department has hosted an African American Read-In in February to celebrate Black History Month. Taking inspiration from the NCTE event, we invite a published writer from the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area (the DMV) to our school to read from their body of work, share anecdotes about their writing journey, and offer encouragement to an audience of young writers. The purpose of the annual program is threefold: (1) to foster an appreciation of literature, (2) to shine a literary spotlight on favorite Black authors, and (3) to create valuable learning experiences that lead to stimulating conversations about literacy and diversity. To that end students and staff are also encouraged to read pieces written by Black authors. For more than 10 years I have written and read an original poem at Broad Run’s Read-In. While I was working on the manuscript for purl (2025), my first poetry collection, I realized I had another collection forming. februaries not only celebrates the literary contributions of Black writers connected to the DMV but also chronicles my growth as a poet.

How did you hear of Yellow Arrow? What inspired you to submit your chapbook?

In early 2023 I was an emerging poet actively searching for a writing community or organization in the DMV when I saw a post from Yellow Arrow on Instagram. As a graduate of Smith, a woman’s college, Yellow Arrow’s commitment to amplifying women’s voices was appealing to me. Later that year I submitted a chapbook manuscript of poems for consideration. Because it was shortlisted, I decided to send “malea,” one of the poems from the manuscript to the submission call for Yellow Arrow Journal ELEVATE (Vol. IX, No. 1). They accepted my poem and took great care preparing it for publication. After ELEVATE’s release, Yellow Arrow invited me to read at their online launch for the journal and also featured me in their .Writers.on.Writing. feature. Since februaries celebrates writers connected to the DMV, I am thrilled Yellow Arrow, a Maryland press, is bringing it into the world.

Can you talk about the cover selection process?

The art on the cover was created by my son Harrison Evans (Instagram @yatsby_harry999). He is a self-taught artist currently finishing a tattoo apprenticeship. In many ways both of us are emerging artists, and I am committed to spotlighting him and his creative gifts whenever I can. Harrison also drew the cover of purl and all the art on my website, awordsmithie.com. I am so appreciative to Yellow Arrow for giving me the opportunity to use his art for the cover and interior pages. Because februaries pays homage to the literary contributions from DMV creatives, I asked Harrison to include something that represents the region. After reading the poems penned for my school’s Black History Month annual event, Harrison drew a landscape of the Washington Monument and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Hovering above the buildings in the skyline is a rendering of Aquarius—the water bearer, the zodiac sign for people born from January 21 to February 19 and the figure often associated with intellect and independence, the one pouring knowledge and ideas into the world.

Your poems encompass a broad and intriguing range of historical topics and figures. How did you come to the combination of Rihanna and Maya Angelou for “973.0496”?

I wrote “973.0496” in the first few weeks of 2023. For most of my teaching career, I have maintained a classroom library for my students by purchasing books each school year. To offset expenses I scour library sales, used bookshops, and thrift stores for titles from different genres I deem appropriate for my high school students. In 2023 book bans were on the rise across the country in schools and public libraries, and for the first time in my career, I wondered if my classroom library might be viewed as a liability to some rather than a valuable resource for all. Book banning and the rewriting and erasure of American history were weighing heavy on my mind when I sat down to draft this poem. I often listen to music as I am writing and while I don’t remember the exact moment, I do know that Rihanna’s song “Lift Me Up” from the 2022 movie Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022) was on heavy rotation. The lyrics “lift me up, hold me down, keep me close, safe and sound” were stuck in my head so I scribbled them in my journal. I was torn between using this line and one from Angelou’s poem “Still I Rise” for my first attempt at writing a golden shovel, a form created by Terrance Hayes and inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks. In the end I decided to write a double golden shovel to honor both Angelou and Rihanna.

write, they say, what upsets you, threatens you, paper moon scribbles, raising up

me and others like me with bowed heads, clasped hands resisting earth’s choke hold.

“973.0496”

You bring an impressive array of poetic forms to the pages of februaries. What prompted your experimentation?

Even though februaries is my second book, I still feel like I am an emerging poet, one who is still trying to discover a signature voice and style. Because of this I am always experimenting with form. In this collection readers will find many forms including several invented by Black writers: the duplex, skinny, eintou, and golden shovel. Each section in this chapbook includes a skinny poem inspired by the featured read-in writer and a tribute poem that I wrote after the event. I especially enjoyed experimenting with the skinny form, which was invented by Truth Thomas in a Tony Medina Poetry workshop at Howard University in D.C. For each skinny poem, I treated the first and last line like a cento by borrowing a quote or a verse from (most of) the tribute poets. Harrison’s art and the skinny poems are like bookends for each year and section.

Let’s talk about “can I buy a vowel”? What experience would you like this form to awaken in your audience?

In 2019 Broad Run High School invited Camisha L. Jones to be our featured speaker for the read-in. She read several poems from Flare (Finishing Line Press, 2017), her chapbook about her personal experience with hearing loss and chronic pain. I was moved not only by her verses but also by her resilience in the face of what she names an “invisible disability.” My poem “can i buy a vowel?” takes its inspiration from the line “Being hard of hearing is kinda like filling in the blanks / of a Wheel of Fortune puzzle” from her poem “The Sound Barrier.” All the e’s have been removed from lines of my poem, which makes it more challenging to read. By attempting to show on the page how it might sound to someone with hearing loss, I hope readers will remember everyone is battling something. And sometimes those battles are invisible. “can i buy a vowel?” is a reminder to extend grace, understanding, empathy, kindness, and love because we never know what someone is going through. I also hope that those battling visible and invisible disabilities will be encouraged by the poem’s message.

There is an abundance of powerful and lyrical imagery in your poetry. Can you expand a bit on what drew you to the nature imagery in “dark, and lovely, and limitless”?

My children gifted me a small African violet for my birthday the year I wrote “dark, and lovely, and limitless.” Because my birthday is the day after Valentine’s Day, the floral selections in shops are often picked over. The ubiquitous red or pink rose bouquets with baby’s breath have been replaced with plants like violets, kalanchoe, and cyclamen. Little did my kids know their selection was quite appropriate since African violets are the birth flower for the month of February. When I began drafting this poem for my school’s 2022 read-in event, I was sitting at my desk looking at their gift and battling an episode of writer’s block. Instead of picking up a book to read (my normal remedy), I decided to research care for my little houseplant. That’s when I discovered its scientific name, Saintpaulia ionantha. Seeing images of all the vibrant varieties online reminded me of the famous quote from Alice Walker’s The Color Purple (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982): “I think it pisses God off if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don’t notice it.” Although the flowers in the iconic scene when Celie and Shug are walking in a field of purple are not African violets, that image inspired me to include nature imagery in my poem. I mixed in details about plant care with its East Africa origins in some of the lines. Given how much inspiration I gleaned from Alice Walker who was also born in February, it seemed quite fitting that I wrote this poem as a tribute to her.

she hails from purple mountains majesty

east african fields, her mother’s land

draped in amethyst petals, leaves jaded

in velvet, crowns rooted in smoky quartz

“dark, and lovely, and limitless”

Do you have any advice to share with fellow women-identified writers?

Develop healthy reading and writing habits. My students in my English and creative writing classes read a book of choice or write in their journals for 15–20 minutes every class. I call it Daily Pages. One class they write and then the next class they read. For me it’s about helping them create habits, build stamina, develop their voice, and discover favorite genres and authors. Ironically, I should have been listening to my own advice and applying those lessons to my writing life. Octavia Butler (Bloodchild: And Other Stories, Seven Stories Press, 1995) once said this about habits: “First forget inspiration. Habit is more dependable. Habit will sustain you whether you’re inspired or not. Habit will help you finish and polish your stories [and poems]. Inspiration won’t. Habit is persistence in practice.” A second piece of advice would be to join a writing group, take a class or workshop, and/or apply to a writer’s retreat or residency. Carving out time in your schedule to focus solely on writing and surrounding yourself with other writers has been so helpful to me.

wake up because everything isn’t black or white.

wake up because bad things happen

when you ignore right from wrong.

wake up because only a fool’s mate wastes precious seconds.

wake up because enough is enough.

wake up because a draw won’t do this time.

“run the ‘gambit’”

Are you working on or planning any future projects you’d like to share with our readers?

For the last two years I have spent a lot of time preparing two different poetry collections for publication, learning how to market them online using social media, and calendaring readings, interviews, and craft chats. While it has been nice to be booked and busy, I am excited to slow down a bit and get back to spending time just reading and writing. During the pandemic, I paused working on a long fiction project that has been in progress for more than 10 years. Although it will be nice to read and write without hovering deadlines, I can’t forget what Toni Morrison said, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write.”

Thank you Michele and Melissa for such a thoughtful conversation. You can order your copy of februaries from Yellow Arrow Publishing at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/februaries-paperback and find out more about Michele Evans on her website at awordsmithie.com and follow her on Instagram @awordsmithie.

Michele Evans, the author of the poetry collection purl, returns with februaries—a chapbook of poems inspired by her participation in the National African American Read-In (AARI) founded by the Black Caucus of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE). Chronicling and preserving the achievements and contributions of ancestors Harriet Tubman, Billie Holiday, Maya Angelou, and others, februaries, a museum constructed of poignant poems diverse in form, reminds readers: Black History is American History, and it should be “celebrated, appreciated, and narrated” well beyond the annual 28-day observance.

Inspired by the literary tradition established by an assembly of living legends from the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area, such as Dr. Joanne V. Gabbin and E. Ethelbert Miller, Evans, a fifth-generation Washingtonian (D.C.) and English teacher, revisits significant and complicated moments from America’s past to spark necessary and challenging conversations about the future of humanity.

Melissa Nunez makes her home in the Rio Grande Valley region of south Texas, where she enjoys exploring and photographing the local wild with her homeschooling family. She writes an anime column at The Daily Drunk Mag and is a prose reader for Moss Puppy Mag. She is also a staff writer for Alebrijes Review and interviewer for Yellow Arrow Publishing. You can find her work on her website at melissaknunez.com/publications and follow her on Twitter @MelissaKNunez and Instagram @melissa.king.nunez.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Spotlighting Clara Garza: Yellow Arrow Journal X/02 KAIROS Cover Artist

By Darah Schillinger

Clara Garza is a 16-year-old writer and senior at California State University, Los Angeles. She serves as a politics and world health journalist with The Borgen Project and contributes editorially to numerous journals. Her creative and critical work has earned recognition across essay, photography, performance, and visual arts contests, including in statewide and national outlets like the NOAA and KCACTF. Clara is also the cover artist for the second issue of Yellow Arrow Journal, Vol. X, on KAIROS, guest edited by Darah Schillinger. The issue comes out on November 11 and is currently available for preorder at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/yellow-arrow-journal-kairos-paperback. KAIROS explores the aftermath and aftereffects of catalytic moments, forged from either small flash fires or conflagration, and is a Greek word meaning an opportune and decisive moment.

Make sure to take your time exploring Clara’s beautiful mixed-media collage, “The Awakening Aperture,” on the cover of KAIROS. According to Clara, “The circle (inspired by the aperture of a camera, or the lens that captures a fleeting fragment of time) is composed of pieces of the diary of a fictional college student experiencing college life, from the day she is accepted to the school to her graduation. Her initial doubt is reflected by the moody outer rim of the circle, and as she opens herself to the brightness of college, she starts to appreciate her life more fully.” Thank you, Clara, for sending us your artwork and for letting us showcase it to our community.

Recently, Clara answered some questions about herself and her aspirations from Darah.

“The Awakening Aperture” beautifully captures a decisive moment through both concept and form. What first inspired this piece, and how did it evolve from idea to execution?

This piece originated from a college art project prompt that focused on empowering dreams and transforming lives. Since the deadline was the following day when I first received it, I found myself feeling like I could make it—especially since I did not want to take the easy option of painting a college graduate with outstretched arms looking toward the sky. The ending of that story felt too static for me. That evening, I stood just outside my house, pondering how I could incorporate my major (English) into the work of art. A few minutes passed, and the visual of a collage made of literary quotes flashed in my mind. Had I continued with that idea, the paper would have been white, and the camera would have been positioned so that the edges of the collage were not visible. “How would that be empowering dreams or transforming lives?” I thought. Shortly after, I conceived the idea of transforming the quotes into diary entries, and the author into a student who undertook the task of creating an aperture into one of the most transformative experiences of her life. The construction of the piece involved collage, aging techniques, and a sense of symmetry. Each diary strip was individually written, cut, and placed to follow the aperture’s form. The aperture is the symbol of zooming in on one’s own potential more clearly.

As a writer, journalist, and visual artist—is there a particular medium that feels most like home to you? Or is it freeing to switch between them?

I feel nomadic in my eclecticism: The entire world of expression feels like home to me; it is just a matter of circumstances and my personal sense of desire to identify where I will be residing for the night. In that way, I could not imagine, not switching between them—and quite a few more!

What most often inspires your visual work? Are there specific artists, places, or experiences that consistently fuel your imagination?

Funnily enough, I do not know. The most consistent fuel for my imagination is being alone, especially when standing right outside my house in the evening. I can never quite predict when the next idea will come.

This journal issue explores KAIROS—an opportune or decisive moment. How does your piece engage with this idea, especially in the context of memory, self-discovery, or growth?

I believe in the poise of the littlest moments in great endeavors. It is up to the individual to find the kairos in what they remember, do, and desire for the future. There will never be a “perfect” moment to do something, and time is always of the essence, so being opportune and decisive converts ordinary time into meaning.

Your use of mixed media—sewing supplies, suede, torn paper—adds a tactile and almost archival feel to the work. What role do material textures play in conveying the emotional landscape of the diary entries?

Textures create a feeling. Mixed media pop out of an image. These domestic items feel like home to me and hopefully to many others. In monetary value, they might not be worth more than a few cents. In this sense, the diary entries could be from anyone. Through arrangement, these feelings become more immediate to observers.

The circle in your piece acts as both a literal and metaphorical aperture. Why did you choose this symbol and what does it reveal about how you perceive time or change?

Pictures are still, but apertures see all even when the camera is not on. They understand the shift between shadow and light that forms every act of creation. In that space between what is captured and what is lost the still becomes living and perception becomes creative awareness.

There’s a quiet optimism in how the college student character moves from doubt to belonging. What message or emotion do you hope viewers take away when they first encounter “The Awakening Aperture” on the cover of Yellow Arrow Journal?

I hope the viewer feels drawn into the light of the future and acknowledges the beauty in darkness. I hope they see that fragments make up a meaningful whole and that the past continues to grow with you as a reflection, since it will never be quite over, and that they strive to foster the continuation of many awakening apertures of their own.

As a politics and world health journalist with The Borgen Project, how does global advocacy influence your art, if at all?

I often think about how the number of successful individuals with a fortunate upbringing reflects the number of those with unanswered potential who lack the resources to pursue their passions. In that sense, I plan to continue using my platform, which combines artistic and journalistic voices, to draw attention to and advocate for action on behalf of many individuals facing unfair circumstances. This is a continuing cause we must recognize as long as it persists.

Given your editorial contributions and contest success, what advice would you give to other young creators trying to find their voice?

Random thoughts are artistic superpowers. Never dismiss them—listen to them. They are prompts in themselves. How might two intertwine? There is no such thing as not belonging in a particular realm of thought, nor is the lack of specialization a valid excuse for not finding one’s voice somewhere new. Your career(s) should be your passion, and your passion is invaluable to the world. You are not just another child with a dream. You have potential. You can pursue many things deeply if they move you. Take a step back from life and look at yourself like the protagonist in a fantasy story. Analyze the decisions the protagonist makes; the reality is that every decision has strengths and flaws. Do not stop at saying that you could have done something different, better, or worse. Take action and stay unpretentious throughout the process. Have fun sharing what you have done. It is never too early or too late to rethink the direction you are going in because 360° of possibilities will always be around you.

What’s next for you—creatively, academically, or professionally? Are there any upcoming projects you’re especially excited about?

I am applying to pursue a master’s degree in screenwriting. Since film requires a mastery of artistic awareness, I am excited to leverage my eclecticism to write impactful movies. Film feels like a natural extension because it combines story, picture, and emotion within a single medium. An upcoming project I look forward to is my thesis on the subtle presence of ideological reinforcement and dismantling in children’s literature. I am also excited about my visual and literary works being accepted into more journals.

Thank you Clara for finding the time to answer our questions and for being a part of KAIROS. And thank you to everyone for supporting the creatives involved in the issue. You can preorder your copy of KAIROS at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/yellow-arrow-journal-kairos-paperback. If you want to reserve a copy of both issues of 2025, make sure to pick up a discounted journal bundle at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/yellow-arrow-journal-bundle, for yourself or as a gift.

Darah Schillinger (she/her) is a writer based in Lexington Park, Maryland. Her poems have appeared in AVATAR Literary Magazine, Yellow Arrow Journal, Maryland Bards Poetry Review, Empyrean Literary Magazine, Grub Street Magazine, and Eunoia Review and on the Spillwords Press website. In October 2024, her poem “An elegy for the Pompeii woman the Internet wants to fuck” was named a finalist for the Montreal International Poetry Prize. Her first poetry chapbook, when the daffodils die, was released in July 2022 by Yellow Arrow Publishing. Her second collection, Still Warm, is a work in progress.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Unsettling the Silence: A Conversation with Vic Nogay

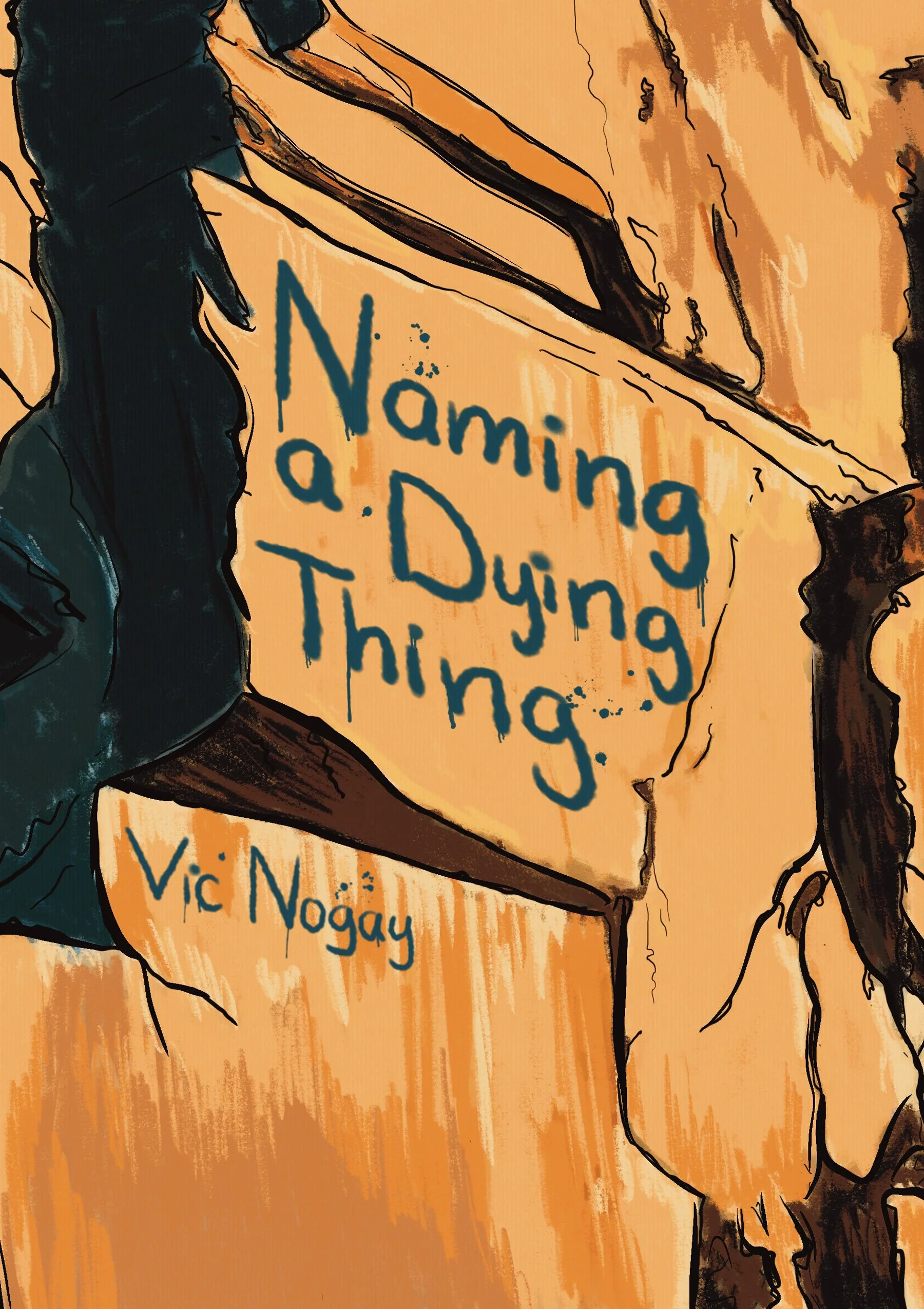

Poetry is often born from tension—the space between beauty and loss, the sacred and the ordinary, the personal and the political. In her soon-to-be-released poetry collection Naming a Dying Thing, Vic Nogay invites readers into this space with a voice that is at once lyrical and unflinching. Her work lingers on themes of motherhood, loss, and nature, encompassing the cycles that both sustain and unsettle us.

Nogay is a writer, reader, and editor from Ohio with a richly variegated publication archive (find out more at vicnogay.com/publications). Her second poetry collection, Naming a Dying Thing, to be published by Yellow Arrow Publishing in October 2025, is a reckoning with memory and present experience woven together as a “tarnished treasure” of the self. This collection reflects our mission while carving a powerful place for itself in contemporary poetry. You can get your copy of Naming a Dying Thing at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/naming-a-dying-thing-paperback.

Melissa Nunez, Yellow Arrow interviewer, and Nogay connected with each other to discuss the inspirations behind Naming a Dying Thing, the role of sound and rhythm in her work, the push-and-pull of modern motherhood, and the grounding force of nature.

I am trying to find wonder in the world, but I have

driven many highways, seen you flayed, our names

in paint, sprayed and slipping down the length of you.

“Appalachians”

Who are some of your favorite women-identified writers?

Toni Morrison, Maggie Smith, Louisa May Alcott, Tess Taylor, Alison Stine, Tiffany McDaniel, Natalie Babbitt, Kalynn Bayron, Amy Turn Sharp, Tiana Clark, R. F. Kuang, Claire Taylor, Amy DeBellis, Madeline Anthes, Barbara Kingsolver, Gabrielle Zevin, Amy Butcher, Gwendolyn Kiste, and Rachel Harrison . . . just to name a few!

How did you discover Yellow Arrow Publishing? What inspired you to submit Naming a Dying Thing?

I can’t say for certain, but I’m pretty sure I discovered Yellow Arrow on Twitter back when it hosted a thriving literary community. I submitted this collection to Yellow Arrow and a select few other presses whose missions aligned with my own. I love that Yellow Arrow is a nonprofit indie publisher that puts their mission at the forefront of who they are. A press that vocally and proudly exists to champion all women-identified writers is a community I am so grateful to be a part of.

What inspired the creation of this poetry collection?

The pandemic unlocked some kind of portal in my brain that sucked me back into a creative writing practice I had been avoiding for years. It forced me to reckon with a past gilded by time and memory, as well as my more present experiences with motherhood, marriage, miscarriage, and general political/social chaos. Over the past five years, my writing has returned to the same topics, turning them over and over again looking for answers that don’t exist. At least I haven’t found them yet. Having these pieces together in one collection is like holding a piece of my soul in my hands, a record of my life. A tarnished treasure, but treasure all the same.

Can you walk us through the cover selection process?

As a reader, I love closing a book and returning to the cover with new eyes, finding nods or clues the author gave us right from the beginning, and I wanted readers to have that same experience with this collection. I discussed this concept with [Yellow Arrow Creative Director] Alexa Laharty, and she was totally on board! We explored several images in the collection and felt the spray paint on the blasted mountain rock face was unique, evocative, and representative of the collection as a whole.

I’m holding you and my breath

while your big bluestem heart beats

under thunder and a sturgeon moon.

“Now you are six”

There are many strong themes in this collection, one of which is motherhood. In your opinion, what does “motherhood” mean in a modern society? What has changed and what has remained the same?

For me, motherhood is like breathing—a constant oscillation between restriction and expansion, limitation and growth. I find my experience as a mother to be healthiest and most fulfilling when I remove myself as much as possible from the context of our modern society. It’s impossible to do, of course, but the effort is worthwhile. I find modern expectations of motherhood do not embrace the essential push/pull, only the push, only the expansion, only the expectations. Modern society offers mothers no relief. My resistance is in taking relief wherever I can find it.

I was struck by the balance of beautiful lyricism with a brazen, unadorned honesty in your poetry (e.g., “Testimony” and “Folk tale”). What drew you to this contrast in voice?

A change of voice within a poem is often striking, even unsettling. When I employ this change, I deliberately want to unsettle. Unsettle the poem, unsettle the reader, unsettle myself, unsettle the systems that confine us. It’s a hex on injustice and those who wield it like a weapon. I hope it feels like the curse it is intended to be.

I love the skillful use of alliteration, assonance, and repetition in poetry. My eye was drawn to words connected to the concept of the “sacred,” words like “hallow” and “burrow,” which appear in multiple places in multiple forms in this collection. Can you speak to the allure of these words/concepts for you?

I think words with two vowel sounds split by a double consonant have always felt so rich and warm and earthy to me. I like the contrast of exploring the ethereal, sacred, and unknowable with words that feel tangible, resonant, and specific. Contrast gives a poem anticipatory movement. The sounds and rhythm of words are as important as their definitions.

At ten weeks, for six days, I labored;

my body exiled my body.

When it was over, I did not look

but let my love hallow

“Testimony”

Another thread apparent in this collection is love and relationship. In your opinion, how does love both connect and divide us from others? How does this play out in marriage and in parenthood?

Woof, this is a tough one for me. I have no authority to speak on this topic. I’m just fumbling through it all. The poems are as close to opinions as I get.

The cycle of growth and decay in nature is very present in the imagery of your poetry. How does this speak to patterns in our personal lives?

I grew up very disconnected from the natural world, and I think this lack of familiarity or understanding created a dependence on the heavily curated, manufactured illusion of reality in suburban America. Even now, I’m not a skilled outdoorswoman by any stretch, but the time I’ve spent learning about and caring for native Ohio plants and wildlife has connected me to it all, removed the flimsy false barrier between humanity and the rest of this one earth. The natural life cycle, and feeling acutely a part of it, has been surprisingly comforting and inspiring.

light me up & listen

for the passerine,

furious & thrumming—

ten thousand tiny bird wings

out of my mouth.

“birds are singing in december when you say that you are leaving me”

Aside from writing, you are also an editor at Identity Theory and have worked on editing for other publications in the past. How does that experience compare to working with Yellow Arrow on your own personal collection?

It’s fascinating to switch sides! As an editor, I feel very confident and responsible for supporting the writers I publish. It feels a little intimidating to be the writer in this scenario. Like, who am I to publish a book? I wish the editorial confidence carried over to my writing persona!

Do you have any advice for fellow women-identified writers?

I feel a deeply ingrained pull to see and consider multiple perspectives of my own life and experiences. But when I’m writing that inclination dissolves. What am I saying? Poetry is not diplomatic; the only person your words owe a voice to is you.

Do you have any hobbies outside of the writing world that help bring balance or peace to your mind and life?

Oh yes. My dear sweet chickens! I have 11 bantam hens that are just entering their first laying season. Caring for them daily feels so essential. I feel so small and indebted to them. I love cleaning their coop, watching them forage, talking with them, and snuggling. I have never felt a peace like this.

Are there any future projects you are currently working on you would like to share with our readers?

I am at work on my first novel. It’s a ghost story, but that’s all I can tell you for now!

Thank you Vic and Melissa for such an engaging conversation. You can order your copy of Naming a Dying Thing from Yellow Arrow Publishing at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/naming-a-dying-thing-paperback. You can find out more about Vic Nogay online @vicnogaywrites.

Like humid Ohio summers, often wistful and lovely, yet undeniably heavy, Naming a Dying Thing by Vic Nogay is a sticky collection. At times a confrontation, at others an abdication, the poems within this offering reckon with the roles of women and mothers in a society that demands they be somehow everything and nothing all at once. Naming a Dying Thing contemplates and subverts success and failure in love and in life, holding both up to a hostile American reality. There are no answers here.

Nogay is a Pushcart Prize and Best Microfiction nominated writer from Ohio. She is the author of the micropoetry chapbook under fire under water (tiny wren, 2022) and is the microeditor of Identity Theory. With Naming a Dying Thing, Nogay avows the labor of motherhood and loss, bears the weight of a changing world, and unspools the taut line of memory, leaving the frayed edges to rest out in the sun.

Melissa Nunez makes her home in the Rio Grande Valley region of south Texas, where she enjoys exploring and photographing the local wild with her homeschooling family. She writes an anime column at The Daily Drunk Mag and is a prose reader for Moss Puppy Mag. She is also a staff writer for Alebrijes Review and interviewer for Yellow Arrow Publishing. You can find her work on her website at melissaknunez.com/publications and follow her on Twitter @MelissaKNunez and Instagram @melissa.king.nunez.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

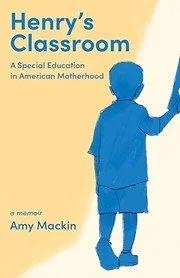

Amy Mackin on the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Her Publishing Journey

“It’s really a labor of love”

Amy Mackin writes at the intersection of education, cultural history, public health, and social equity. Her work has appeared in outlets such as The Atlantic, Chalkbeat, The Washington Post, Witness, and The Shriver Report. She earned her MA in American studies from the University of Massachusetts and her MFA in nonfiction writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Over the last several years, she has held leadership writing roles in the public health, science, and higher education sectors. Mackin loves the fickle weather and spectacular landscapes of New England, where she resides with her family and always at least one friendly feline.

In a recent conversation with Yellow Arrow summer 2025 publications intern Kate Tourison, Mackin reflects on the unexpected challenges and heartfelt successes that came with publishing her memoir Henry’s Classroom: A Special Education in American Motherhood with Apprentice House Press this past spring.

With Henry’s Classroom, Mackin combines her family’s personal experiences with years of research, exploring the medical, social, and educational barriers her son encountered during early childhood, ultimately revealing a larger story of ineffective systems that are failing millions of families across America.

“My son, who I call Henry in the book, was diagnosed with developmental delays at 16 months old, which set us on the journey of engaging with early intervention services and then moving into the special needs preschool, and then from kindergarten through fifth grade with the district's special education program,” explains Mackin. When reflecting on the publication process, Mackin relays some of the difficulties she encountered, starting with submitting her work, stating that “that’s probably the most difficult part.” Mackin reached out to a number of literary agents, wanting her story to be published by big-name companies like Penguin Random House or Simon & Schuster. The querying process, however, was much more challenging than she had anticipated.

“I had two agents respond to me, both of whom I admired their work and would have been thrilled for them to have represented the book, and they both asked for additional pages, then they both asked for the full manuscript, and ultimately they both rejected it,” Mackin says, laughing. “One said there was too much research in the memoir for them, and the other said there was not enough research in the memoir for them.”

Finally, Mackin chose to pivot. “I had decided that I was going to take a break because I had been kind of worn out by the process, but I had a couple of friends who had had really good experiences with small presses, so I decided I was going to go that route.” As she began looking into independent presses, Mackin stumbled across Apprentice House Press, a student-run book publisher located in Baltimore, Maryland.

I had never heard of Apprentice House,” she explains. “But I said, you know what, I'm just going to submit and see what happens, and then I heard back from Apprentice House maybe six weeks later, saying that they were actually interested in publishing it. I was thrilled.”

For Mackin, this had been a long time coming. Henry’s Classroom had started as a project for her MFA, and it had gone through several subsequent iterations and genre changes before Mackin began thinking seriously about publication. “Writing, you know, it was very much a solitary, isolating thing, generally. Even with me, I was in a low-residency MFA program for some of this, and once that ended, I didn't have a local writing group or anything like that to bounce these kinds of ideas off of, so it was very, very isolating. It’s very uncertain about, you know, the quality of what you’re putting out there, if people will resonate . . . you’re not really sure if you told the story or gave the story, honored it the way you wanted to, and so it’s been incredibly validating for me hearing some people’s reaction to the book.”

After having signed with Apprentice House, Mackin spent the next year working on a final draft for publication. On May 6, 2025, Henry’s Classroom became available to the public. But the work did not end there—for Mackin, marketing and publicity was half of the battle.

“I did hire an independent publicist. It is really expensive, I mean, I think that needs to be out there. I purchased the amount of services I could afford, and I ended it at that. It was helpful, but I do also think that you can do it yourself, just because I think when you’re publishing with a small press, you’re typically not getting an advance . . . you’re doing all the editorial work, and all of the publicity work, the writing, in your spare time. And a lot of us are introverts by nature, and we’re not really comfortable self-promoting. So I mean, you only do it because you really believe in the story you have to tell, and you really believe in the power of books. It’s a lot, and you know, it’s really a labor of love,” she concedes.

Ultimately, Mackin boils it down to two primary objectives. First, realizing your target audience:

“I made a decision pretty early on that I would [be] helping other families navigate this, or sometimes just letting other families or parents vent about the frustration of the system. So I’m interested in engaging with educators, and parents and families, and I’m kind of targeting that group. I did a book launch event, I’ve done a couple of book signings where people came out and wanted to talk about these things, and it was great. Just last week I actually spoke at an international conference on maternal scholarship, and the reactions have been really, really positive, and it’s led to really great discussion. That’s been probably the best part of all of this, just the conversations I’ve been able to have.”

Mackin’s second piece of advice is to look to other successful writers for inspiration: “Find books similar to yours that have been published with a similar size press and see where they’re getting promoted. And then, you know, contact those podcasters, contact those magazines, those newspapers, and say, ‘Hey, I saw that you covered this book, I write in a similar vein, wondered if you’d be interested in doing a feature on this.’ A local press is definitely your friend when you’re an independent author, and your local communities are going to want to support you.”

In addition to nearby news outlets, Mackin turned to her local booksellers and librarians. “I took my book, and I kind of drove around maybe a 90-minute radius as soon as the book came out. I talked to independent booksellers and many were very willing to consign my book and put it on their bookshelves, and also to have a book talk or a book signing event with me.”

When asked if there is anything she would have done differently, from start to finish, Mackin offers one last piece of wisdom to writers in her position: “I wish that I had entertained the idea of a small press publication sooner,” says Mackin. “I think a lot of writers feel like the goal is to get a literary agent, to publish with one of the Big Five, to get those reviews by the big industrial reviewers, all of that. And I think that is a laudable goal for a lot of people and is appropriate but depending on what your goal is for your own work, really think about that. Because for me, this meets the goal that I was trying to get to. And, getting published with a Big Five wouldn’t necessarily. I am so grateful that this book is out in the world now and is allowing me to have these conversations in a larger way that I know it's helpful to me and I feel like has been helpful to other people.”

You can find Henry’s Classroom: A Special Education in American Motherhood, published by Apprentice House Press, at Bookshop.org. Thank you, Amy and Kate, for such a great conversation about publishing.

Kate Tourison (she/her) is a rising senior at Loyola University Maryland where she majors in English and communication with a specialization in advertising and public relations. As a lifelong book lover, she is thrilled to join the Yellow Arrow team and engage with an inspiring community of women writers. During her spare time, she enjoys watching old episodes of Gilmore Girls, taking long walks with her dog, and, of course, reading! You can find her at @katetourison on Instagram.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Where We Are: A Conversation with Ann marie Houghtailing

I will let your heart beat like an ancient drum

and let you feel the suffering place

that can feel like an ocean with no horizon

You may want to run

but I invite you to stay

“The Suffering Place”

The transcendent nature of the written word allows us to see and be seen beyond the boundaries of time. Storytelling allows us to share and shoulder the joys and burdens of humanity, and writers like Ann marie Houghtailing embolden us to embrace this philosophy in our daily lives.

Ann marie Houghtailing is a multigenre writer, visual artist, and cofounder of the firm Story Imprinting. Her debut chapbook, Little by Little, will be published by Yellow Arrow Publishing in April 2025. Today, we are excited to introduce Ann marie along with the exquisite cover of Little by Little. Reserve your copy at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/little-by-little-paperback and make sure to leave some love for Ann marie here or on social media. This collection reflects on layers of loss universally experienced and offers communal suffering as a means of embracing wild resilience. It is a celebration of domestic storytelling that calls us to truly see ourselves, each other, and a world in which we are free to shamelessly grieve all the sorrows of this life—however slight—together.

Melissa Nunez, Yellow Arrow interviewer, and Ann marie engaged in conversation over Zoom where they discussed acceptance and compassion in the creative process and the world.

Who are some of your favorite women-identified writers?

This is an interesting question to answer, because for me, writing and language do not come from my formal education alone, but from the storytelling tradition of the women that I grew up with. I dragged around a complete collection of Emily Dickinson when I was a teenager and studied all the women writers you would expect in college. But the truth is I was surrounded by storytelling my entire life. I grew up among women who “talk story,” a phrase that comes from my mother’s Hawaiian upbringing. They shared their lives through this medium as a way to make sense of their struggles and connect. This might be an unsatisfactory answer, but it is an accurate one. My writing is rooted in the gifts I was bestowed by women in my family and my culture. My sister was a teenager when I was born. She learned words just so she could teach them to me. She wasn’t really engaged in school for herself, but she wanted something better for me. No writer has done more for me than those women who were not formally educated, who no one will ever know, who embraced storytelling as a means of survival. My mother, my sister, my aunties, and my extended family are the people who made me revere storytelling.

That said, of course there are many women writers who have inspired me. Someone who is not a poet, but who I love dearly is Cheryl Strayed for the rawness of her work. I think she’s wildly undervalued. I also adore Maya Angelou, Mary Oliver, Sylvia Plath, and Elizabeth Bishop. But I think that so often these kinds of dialogues miss the domestic storytelling that all my poetry is very much about. This particular group of poems (Little by Little) grapples with the nature of loss and was birthed after losing four members of my family in just over a year.

Can you share more about how these pieces came together as a complete chapbook?

All the poetry was written in response to this year of loss that I mentioned. My nephew died at 44 years of age. He was my sister’s only son. Then, my brother died when I was in Portugal, three months later. Our mom died surrounded by my family in my home nine months or so after that, and then my sister’s husband died a few months later. My sister, in the course of a year or so, lost her husband, her only son, her brother, and her mother. Imagine that. My brother-in-law was somebody I knew my entire life. These weren’t distant relatives; I lost my family. This all happened during the pandemic. No one could come and be with me in my grief. People had to love me from afar.

I was using writing and painting to try to survive and not lose my mind. I don’t think I was considering this as a collection. I was just waking up with poetry in my mouth, writing it down, walking the dog, and then writing again.

When I later looked back, I saw that there were themes about different kinds of loss. I also wrote a poem about a little girl and the loss of feeling perfect when you’re young. You have all this power because you think you can be anything. You can wear all the glitter and a crown while carrying a sword and walk through the world feeling wildly powerful, and then life chips away at you. That’s another kind of grief and loss. Learning to be with loss is a constant thread in life and this collection. It’s broken up into moments, some about death, but others about being a woman and feeling crushed or silenced by restricting expectations. People are grieving all the time: children leave the nest, beloved dogs die, relationships end, and people lose their jobs. I was wrestling with these ideas about loss and what it means to sit inside of grief. There are a million ways in which we grieve, and I think that as a society we’re incredibly uncomfortable with talking about loss and death. We’re typically ill-equipped to be open about grief. Recently, I’ve talked to numerous people who shared stories about friends who cut them off without explanation. That, too, is a kind of grief that is such a common experience that people have so much shame around. Death and loss in all its forms is everywhere.

What drew you to Yellow Arrow Publishing?

A friend of mine, Candace Walsh, published a collection (Iridescent Pigeons) with Yellow Arrow. She posted about it on social media, and it caught my attention. I just thought, “I have all these poems that are sitting around. I’m just going to send them off.” I had read her collection—she’s extraordinary—and started looking through all the material from Yellow Arrow available to read online. It just encouraged me to put my work out there.

Can you talk about the process of creating your cover art?

I’m using my own art, and I sent it to Alexa Laharty (creative director) for consideration. In consort with writing, I produced a series of paintings called the See Jane Project. I did one small painting every single day that I posted and sold. They were small 8-by-10 pieces addressing visibility and invisibility. The name Jane is laden with cultural references. We call an unidentified, murdered woman, Jane Doe. Plain Jane is a phrase used to describe a woman that doesn’t meet cultural beauty standards. There are all these ways in which Jane, as a name, has cultural power that’s largely negative. I wanted to challenge that idea.

All these paintings came with little bios and backstories. None of the bios referenced the relationships in their life. It was all about who they were and their little quirks. If you go to a bookstore there are so many book titles that reference women in relationship to someone else. For example, the Pilot’s Wife, The Bone Setter’s Daughter, and on and on and on. It’s so interesting the way women are valued or defined in terms of their role in a relationship. The cover art is a collage piece of a woman with a typewriter on her head. It came from the same period as the poems, so it felt very right to pair these together.

I will rock in the cradle of sorrow with you

I will stand in the darkness until morning with you

I will go back and back and back to a place I’ve never been with you

“I Will”

Your poems on suffering are truly insightful. I appreciated the different spin on how this concept is usually presented or perceived. What would it look like to sit in someone’s suffering? And what would the world look like if we did more of this for each other?

This is really important to me. I just lost a dear friend. I was with her when she took her last breath. Sitting in suffering is allowing someone to be in pain without judgment or interference. It’s the ability to bear witness. I think most of us want to run away from it because we want people to be okay. It’s hard to witness suffering. To honor the suffering of another is transformational. We’re all guilty of saying that we’re fine when we’re not because we don’t want anyone to be uncomfortable. After experiencing so much loss I would say, “I’m terrible, but I’m sure it will get better.” I could tell that people didn’t know what to do with that. We don’t know how to be okay with people who are not okay.

I remember years ago I was going through a really hard time. I was with a friend of mine in a Target parking lot, and my seatbelt got stuck in the car. I just got so pissed off and was yelling. And she did the most generous thing anybody could have done. She put her hand on mine, and said, “I know you’re super angry right now, and you have every single right to be. Things have been so hard. This isn’t who you are, it’s just where you are, and I’m going to be here with you.” It was the most radical thing somebody could do because people want to shut down or turn away from somebody who is filled with pain or rage or sorrow. We want to tell them they’re fine or it will all be okay. I don’t know that we always need to be cheered up. I think we need to be where we are without shame or apology. There are some things you cannot fix. People will get sick or die, the worst things will happen. People lose their children; their loved one will be drug-addicted or mentally ill. It is agonizing. But being with somebody, just being in it, is not nothing. It’s everything, but most people can’t do it.

It always shocks people, but after all this loss I experienced I did a year of volunteering with hospice. People would say, “Oh, my God! How could you do that? Why would you do that? After all this?” For me it was affirming and made me useful. Being with someone at the end of life is a singular experience. It’s the most vulnerable anybody is ever going to be. It’s honest, pure, and sacred. It’s the most precious place you can occupy. I can think of no greater privilege than sitting with the dying.

I also loved the concept of poetry as food in your collection. From your perspective, how is poetry important for our world?

Everyone who reads poetry knows that it’s the most nutrient rich language. Everything’s packed in there; you’re getting the most out of the language. It’s not an exaggeration to say that the right story or the right poem at the right moment can save you. It’s like medicine for your soul. Poetry is a portal to go deeper and examine what it means to be human. It’s a way to connect with other people who may not even be living anymore. You realize you are part of this greater human experience. You are a person who has a broken heart, as millions and millions of people before you. It makes you feel less alone.

The modern version of this is why people are obsessed with memes, right? There’s something that strikes some little chord in them that vibrates when they hear the right thing. They think, “That’s me. You’re talking to me.” That’s what poetry does. It speaks to us. For me, who is not a spiritual person at all, the closest I can get to spirituality is through poetry.

We did not need bread

nor butter

We feasted only on words

fat with truth

dripping with the warmth of breath

“Feasting on Truth”

Can you share more about your visual art process and how that might speak to you or interconnect with your poetry?

I didn’t know anything about neuroaesthetics until after I’d gone through the grieving process. Then I read about it and understood why I was painting and writing. It was keeping me present. It was definitely the tactile aspect of it for me. I distinctly remember being in my studio and having moments where I couldn’t even use a brush because I didn’t want that distance between myself and the canvas. I wanted to get paint on my hands and under my nails and in my hair. It was a way to hold on to life. All my work is filled with color, which is very much rooted in my mom’s background from Hawai’i. If you look at the room I’m in right now, it’s like an explosion of color. Color is joyful. It’s life affirming. The cross-section of painting and writing were the ways in which this intersection of life and death were coming together for me. Pain coexists inside of life. All my suffering had something to do and somewhere to go. I spent lots of really late nights in my studio making bad art, and okay art, and kind of good art, and none of it mattered. It was process focused. I could feel it making me a little bit better every day, just a little, tiny bit better every day.

Would you like to share about your work with Story Imprinting?

Story Imprinting is the business that I run with my business partner, Holly Amaya. We work with large corporate clients and teach them the neuroscience, application, and structure of storytelling for leadership. They learn how to use storytelling in business development, recruiting, and management. Storytelling is something that humanizes the corporate world, and it helps connect people more deeply than just data, statistics, or fact patterns. Whether you’re talking about how to give somebody feedback or how to deliver a keynote or a presentation, storytelling is the most powerful tool at your disposal. This is not just my opinion. It’s backed by neuroscience and extensive scholarship. We train large corporate clients all over the country, largely in big tech, big law, and big accounting. Those are primarily the verticals we operate in.

Do you have any words of wisdom for the women-identified writers in our audience?

Writing can be such a tender, fragile thing. There’s an impulse to want to keep it to yourself and not let the world step all over it. The fear of criticism is real. If you want to be true to yourself, you have to turn off that noise. Don’t get me wrong, you need quality feedback. But not all feedback is equal. Writing isn’t for you to stick in a drawer. Writing is for readers. You have to make yourself vulnerable. You cannot be defined by the people who don’t love your work or think your work is garbage. Those aren’t your people. But if you have enough people that support your writing and say that it’s meaningful, that’s all that matters. You don’t need everyone’s approval. You don’t need anyone’s approval to write. You need to write, because that’s who you are. Be brave.

Do you have any future projects that we should keep an eye out for?

I’m currently working on a book proposal. It’s still an infant. It’s also about grief and the creative process. I’m hoping it finds a home. I’ve learned so much from my own experience and will also discuss what some of the research says about how creativity can support the grieving process.

Thank you Ann marie and Melissa for such an engaging conversation. You can find out more about Ann marie Houghtailing and her work at annmariehoughtailing.com and can order your copy of Little by Little at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/little-by-little-paperback. We appreciate your support.

Little by Little by Ann marie Houghtailing explores the universality of human suffering and how we find our way to meaning and purpose. Houghtailing is a visual artist and cofounder of the firm Story Imprinting. She delivered a TEDx Talk entitled Raising Humans and performed her critically acclaimed one woman show, Renegade Princess, in New York, Chicago, Santa Fe, San Francisco, and San Diego. “Little by little” is the phrase that Houghtailing’s mother used to say when things were hard. Things were almost always hard. Houghtailing grew up in a culture of poverty and witnessed violence, struggle, and wild resilience every day. What she did not realize was that her mother’s phrase would become a life affirming strategy. It was a map that took her back to herself when life took so much from her.

From 2019–2020, four members of Houghtailing’s family died in rapid succession, including her mother. Their deaths were an extension of historic and epigenetic trauma that would require her to sit inside of suffering and paint, write, and garden her way through to transformation. Little by Little delves into how Houghtailing was able to find meaning in the suffering by examining the beauty of life itself. Every day we experience loss. The loss of innocence, youth, relationships, jobs, money, confidence, power, life, and hope are in constant play. Learning to sit inside of deep suffering can be intellectually, emotionally, and physically demanding territory that invites us to examine who we are and what we are made of. Little by Little is a way to see, a way to suffer, and ultimately, a way to live.

Melissa Nunez makes her home in the Rio Grande Valley region of south Texas, where she enjoys exploring and photographing the local wild with her homeschooling family. She writes an anime column at The Daily Drunk Mag and is a prose reader for Moss Puppy Mag. She is also a staff writer for Alebrijes Review and interviewer for Yellow Arrow Publishing. You can find her work at her website melissaknunez.com and follow her on Twitter @MelissaKNunez and Instagram @melissa.king.nunez.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Poetry by Proxy: A Conversation with Jennifer Sutherland

“Words smoothly figure an exchange even when the trade is made at gunpoint or by the small print no one reads.”

Jennifer Sutherland is a poet, essayist, and attorney from Baltimore, Maryland. Her writing is elegant, poignant, and marked by her discernment of law and language. You can find out more about Sutherland and her work on her website jenniferasutherland.com.

Sutherland’s book, bullet points, was written after her experience as witness to a courthouse shooting and explores concepts like power and violence, from the personal to the global, from her distinct and intersecting perspectives as lawyer, writer, woman, human. It is a powerful read, especially considering the current political landscape. The unlabeled quotes within this blog are from bullet points.

Melissa Nunez, Yellow Arrow interviewer, and Sutherland engaged in conversation over Zoom where they discussed the evolution of identity and language and the power of poetic voice.

Can you share some women-identified writers who inspire you?

Linda Hull and Louise Gluck are writers I go to again and again. Robin Schiff, Carol Moldaw, Linda Gregerson are also writers I admire. And, of course, I must mention Anne Carson.

Can you talk about the transition from law to writing, to poetry?

I’m not sure I fully transitioned. I still pay the bills practicing law, but not in the same way. I don’t go to court anymore; I'm more of an office person now. I mostly write things for other lawyers, which just works better for me now. I was a writer before I ever thought about going to law school. My parents were both teachers. My dad taught English in Baltimore, so I grew up around his books and around literature. I was drawn to poetry before anything else. I was writing poetry before law school. I went to law school for reasons tied to wanting control over my life after some difficult experiences and because people told me I’d be a good lawyer due to my debating and communication skills. I love the intellectual exercise of the law, but I don’t enjoy the confrontational aspects anymore. I’m more interested in talking about how the law works and why it works a certain way than I am in fighting with somebody over who did what. I stopped writing a lot once I got into law school. I think there’s something that changes in your brain when you start thinking from a lawyer’s perspective. Lawyering is very much about shaving things down into small pieces that you can then do away with, and poetry is much more about expansive thinking and considering what I can bring into a topic or subject. I would write little pieces here and there for years when I was practicing actively, but it was after the [courthouse] shooting that I truly came back to poetry in a devoted kind of way. I think it saved me.

What is the process of writing something like bullet points? What was the process of creating the lyric which reads more linear as compared to a collection of shorter stand-alone pieces?

In 2018, I walked away from practice almost entirely and did an MFA in Roanoke, Virginia, at Hollins University. While there, I kept getting close to writing about the shooting, but I couldn’t find the right words or approach. I wrote a lot of poems about other things, and then the pandemic happened during my last semester of my MFA. I think it was the first pandemic winter, so probably February of 2021. I had read Maggie Nelson’s Bluets recently, which is also an important book to me. There was something about the way that she organized that book. It’s written in these little chunks of text, one to a page, and that container was very appealing to me. I digested that book a little bit, and I woke up one weekend morning and had the first line for bullet points. I grabbed a notebook and started writing and most of the book came out basically over that weekend. I wrote it in one extended session. Then I spent months and months after that working with what I had, taking things out, reshaping things, figuring out what the stanzas were going to look like. But substantively, it came out in one chunk, and I think that’s because I had just been cooking it for so long that once it was ready, once I had the shape for the stanzas, it was there.

“Verse lets me throw my voice in a way that prose does not, and I cannot stand too near or my voice will scream at me.”

You make an interesting statement in this lyric about only being able to write poetry. What is the difference between the truth of a story or essay and the truth of a poem for you?

That line is still very true for me. I would love to be someone who can write fiction. I read a lot of fiction, but my brain just doesn’t seem to work that way. Voice is very important to me in my work. Voice is an important aspect of the work of a lot of the poets that I read. I think that has something to do with how lyric works in general. Lyric poetry is like a voice suspended in space without the passage of time. Something about that position, that suspension, allows me to speak. It feels safer.

You also make interesting use of language (legal language and definitions) and commentary about language in cyberspace. How does this new medium of communication/expression impact language for you?

Thank you for picking up on that. I don’t think a lot of people have picked up on this sort of second body/proxy body idea that is in the book. As a lawyer, I’m used to working with abstract entities that are not necessarily people, whether that’s a corporation, a trust, or intellectual property. When situating this piece in historical context, which I tried to do, it was important to me to think about the ways that human beings have been figured or proxied in history. Oftentimes that’s been done to reduce risks of various kinds in business. People want to be able to make investments without necessarily losing their personal assets, which is a way for them to do things that are otherwise very harmful. If you think about the Middle Passage and the business in the trafficking of human beings, that business was possible because people could effectively work behind these corporate proxy bodies and protect themselves. That was an idea that I wanted to bring into the book, the idea that we are doing some of these same kinds of things in the virtual world of social media and the Internet. We are allowing ourselves to create these personas, these people in a literal sense. People have alt or fake accounts, and they can post anything they want as harmful as it might be, as awful as it might be without fear of personal repercussions. But we also have these personas, even if we’re writing underneath our own names and our own photos, that we are projecting into cyberspace that don’t necessarily represent who we are in reality. What is that allowing us to do? Why are we doing that? For most of us, it’s not necessarily intentional or with bad motives, but for some of us I think it is. In the book, I’m working through some of that. In the immediate aftermath of the shooting, there were people who were coming at me on social media because I had posted about it. A lot of these were accounts that were just the bird accounts or fake photos and stuff like that who were coming and saying the most awful kinds of things to me. Someone logged on and told me that I was fat. We are able to do that because we can cultivate these second bodies where we give in to and display our worst impulses while in disguise. I wanted to consider that in the book.

“This space makes a whole new country, a world, a fleet of ships with fictitious names and faces, and they swarm the shoreline with their eely words.”

I admire your honesty and bravery in the way you process these experiences. How are you doing with the concept of feeling stuck in that moment or being separate people? Is it still impacting your daily life?

It will always affect my daily life in some way. I’ve learned coping mechanisms and changed my life significantly. Pulling back from practicing law was part of that. My first marriage was also volatile and not healthy for me. My life changed a lot, partly before the book. I met a supportive person who helped me through this process. But I think there will always be that person in the stairwell representing that awful moment. It changes you; it doesn’t stop.

What would you want readers to take away from this book?

The takeaway for bullet points for me would be nuance. Be open to the possibility of many ideas, many meanings, many contributing factors. The title, the stanzas, a lot of the components of this book have to do with our tendency to want to focus on tiny things and the necessity of expanding past that.

I love your range, from lyric and prosey poetry to pieces more succinct. Talk to me about numbers, which I believe is alluded to in your lyric. “8bsolute” is such a compelling poem visually and otherwise.

I have a couple of pieces with numbers. There’s a couple of pieces in a manuscript that I’m working on now that’s about a Greek mythological character named Alcestis. I think math is an easy stand in for something that’s objectively truthful (although I don’t know that even math is necessarily objective.) A lot of what I’m doing in my work is figuring my way through objective and subjective, which are ideas that are very important in postmodernism and they’re important in law. I think numbers for me are kind of a stand in for objective truth and the likelihood that even objective truth is subject to interpretation.

“You permit me

2 locate myself in your midst, and you in mine, and 2 complete

7he necessary calculations. Through you 1 acquire —

6ravity. A density 1 can’t aspire to when 1 am more obviously

3yself. No one suspects. They only see what 1 project.”

Do you have any advice you can share with fellow women writers?

Women and women-identified people are very often the people who are doing the work that keeps homes going. For that reason, they often don’t have access to the time and the spaces that are necessary to write in the way that we have often been told that we should. We have all these very impressive novelists from the 60s and 70s who talk about shutting themselves away in attic rooms and writing for six hours a day and all this stuff and claim that is what writers should do. For many of us that doesn’t work in our daily lives. It didn’t work for me in my daily life. I think that the tiny moments when you write down a line or a thought in a notebook—it may take you two minutes—those count. Those minutes can be productive. You might come back to those moments, to those lines a year or five years from now. It may become something that is valuable to you. MY advice is not to think that because you only have five minutes to write something down or an hour to work on something that you shouldn’t bother. You should.

Do you have any new projects in the works you’d like to share with our readers?

I’m still working on that manuscript about Alcestis, a character in Greek mythology, who was given the choice to die instead of her husband. He found out about it, because this is Greek mythology, and you get to find out about things ahead of time. She chose to die instead of him and went down to Hades and then Hercules showed up at the house and sort of had this wild party and went down to hell and brought her back. It’s a very odd story, which I think is what interested me. It’s not completely a tragedy, it’s not a comedy. It’s a weird story that felt like a way for me to start thinking through my experience of domestic violence. I am also working on a collection of poems called Errors and Omissions that is still about this issue of risk and of our wish to avoid it by creating proxies to stand in for us. Both projects are more traditionally-lined individual pieces of poetry.

Melissa Nunez makes her home in the Rio Grande Valley region of South Texas, where she enjoys exploring and photographing the local wild with her homeschooling family. She writes an anime column at The Daily Drunk Mag and is a prose reader for Moss Puppy Mag. She is also a staff writer for Alebrijes Review and interviewer for Yellow Arrow Publishing. You can find her work on her website melissaknunez.com/publications and follow her on Instagram @melissa.king.nunez or Twitter @MelissaKNunez.

Jennifer A. Sutherland is the author of Bullet Points: A Lyric, from River River Books, a finalist for the Eric Hoffer Medal Provocateur and Foreword Indies Poetry Book of the Year. Her work has appeared or will soon appear in Birmingham Poetry Review, EPOCH, Hopkins Review, Best New Poets, Denver Quarterly, and elsewhere. She earned her MFA at Hollins University, and she lives and works in Baltimore.

*****