Finding Strength in Our Struggles: A Review of Vic Nogay’s Naming a Dying Thing

By Hannah Bishoff, written November 2025

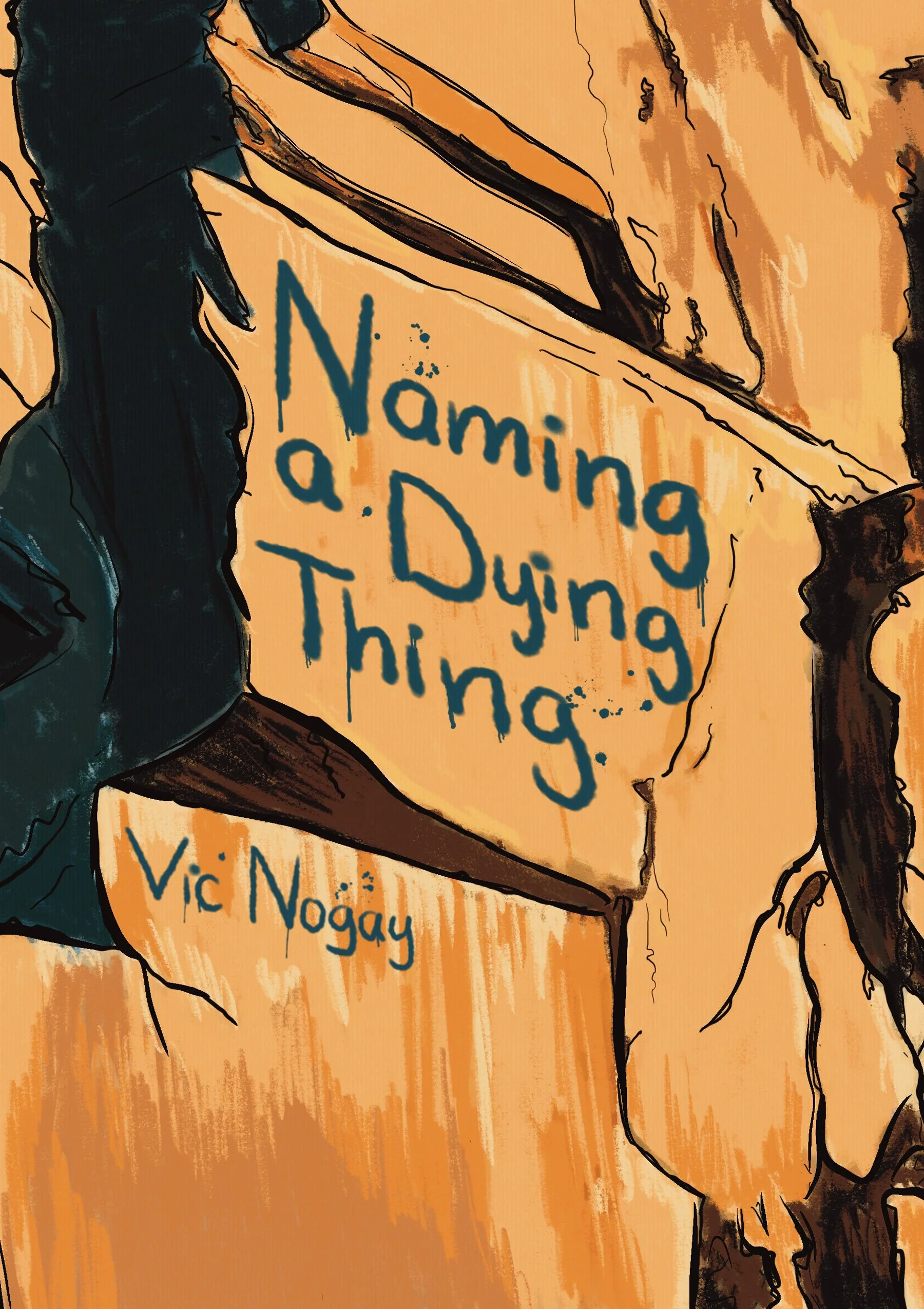

In October 2025 Yellow Arrow released its third chapbook of the year: Vic Nogay’s Naming a Dying Thing. As Nogay is from Ohio, this collection reflects the stickiness of humid hometown summers, where all heavy senses remain heightened. The daunting weight of womanhood is potent throughout, intersecting with everything it means to be a woman, including pregnancy, motherhood, miscarriage, reproductive rights, love, and more, all while reminding the reader of our deep roots in nature. You can purchase the collection at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/naming-a-dying-thing-paperback.

Nogay is a Pushcart Prize and Best Microfiction nominated writer. She is also the author of the micropoetry chapbook under fire under water (tiny wren, 2022) and is the microeditor of Identity Theory. If you want to learn more about Nogay, read this conversation between her and Melissa Nunez, Yellow Arrow interviewer, about her latest collection.

This chapbook is special to me not only for its intense content but also because I had the pleasure of doing some editorial and promotional work prior to its release as an intern with Yellow Arrow during the fall 2025. I inherently feel an attachment to it as it is my first real experience with a publication as an intern, and I will be forever grateful that Naming a Dying Thing is that first for me.

While reading the chapbook very closely, and rereading it many (many) times, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of melancholic longing for something I have never known. Be it the unborn child of “Folk tale” (“When the snow melts / the berries hallow the earth; / I check the spot every spring to see / if there’s a baby growing from the ground”) or “Atropos, Goddess of Fate, Faces Her Own” (“I want to tell [the midwife] to stop, that its no use. I was never meant to be a mother. You are not my fate.”). Or the almost-love of “No point in keeping secrets,” as Nogay confesses, “I’ll always wish you’d’ve given in first so I could have made you feel my body ringing beneath the surface of my skin, quaking the roots of the tree where we slept.” Or even just the dreamy, pensive atmosphere of the depths of Ohio’s summers in which Nogay so eloquently creates, like in “a place,”

you sit in an old canoe,

washed ashore decades before,

and lick your lips

while cicadas sing

and fireflies hang in the humidity—

a summer snow globe.

The whispering reminder of our interconnectedness with nature is what brings each poem together as a sort of journey in taking back what it means to be a woman, to be alive, while coming to terms with it in the meantime. In “Testimony,” Nogay recounts a miscarriage, confessing:

We bound a clot with cloth

and thyme and earthed it

between the ancient roots of the sugar maple

and the fruitless, shallow juniper.

I flushed the rest.

What else was I to do?

Her later promise in “stillborn” of “regrow[ing] / perennial / come spring” evokes a reassurance of serenity, of everlasting light in times of darkness. This depiction of nature binding us, reconnecting us, with lost loves and memories of past selves is a beautiful one and brings forth, almost, a feeling of empowerment. With this is the image “Paraphyly” illustrates: that “we have buried [our fears] deep beneath / the earth to soften your step.” It is further empowering, then, when Nogay exclaims, “we don’t need to be hard to be strong.” The struggles and fears of women and mothers before us are what make up the unsteady path of womanhood.

Each poem adds to the chain of advocacy that becomes this collection, which is evermore essential in times such as those of today, our constantly changing modern world and unsteady political climate. Especially in these rocky times, times where the rights of women are being debated over (by men) and decided on our behalf, it is all the more important that the struggles of womanhood be not only understood but, at the very least, regarded as true and valid experiences. It seems that Nogay’s own frustration with this is even mentioned through “The Great Girl Evaporation of 2022,” describing how nothing could stop “[t]he men in charge . . . / . . . from striking us like matchsticks in the dry beds,” but once “[t]he sky lit up like a million suns. . . . It culled us, / body and soul, up, up with the water.” This frustration with the male counterpart is further demonstrated through “Swan Lake,” as Nogay explains, “I do wonder / at all the ways men spit / into nature’s current.” And, while this discontent is indeed relevant, it is nowhere near being the heart of our worries. The struggles of woman are hers and hers alone.

The looming motif of life and enragement over death, too, is a loud one that was never able to escape my mind while reading Naming a Dying Thing. Nogay’s narration is, at times, loud, as well, even as she writes, “i hold my rotted tongue / & hum to the lake / & the mirror of the moon,” all the while “ten thousand tiny bird wings / out of my mouth.” The journey of womanhood continues, then, through this idea of death, as Nogay confesses in “women,” “proof of death made life in me, / turned bravery to wicked wildness.” These two lines are probably some of my favorites in the whole chapbook. It not only points to the literal idea of death through the image of “a deer skull in a shed” held up “like a kindred spirit,” but seems to refer to all of Nogay’s experiences with death, be it miscarriage or the loss of a child, as some sort of epiphanic relief, creating a whole new life in her through the harshness of death. And, if there is anything the reader should take away from reading this collection, I feel it is exactly that. Our struggles, women’s struggles, embody a rather harsh reality, though such an idea is not to deter us; it is only there to make us stronger.

Hannah Bishoff was a senior English major at Towson University with a minor in Business, Communications, and the Liberal Arts. On the weekends, she works at a coffee shop in Towson and when not in class she enjoys reading, drawing, shopping, and watching TV. She hopes to continue working in publishing in the (near) future, if all goes well. Find her on Instagram @hannaheb.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we LUMINATE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook and Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.